Chapter 1

Notes:

🚨 click for cws

violence, references to famine and regional hardship, references to historical CSA, PTSD symptoms, discussion and depiction of slavery, food and hunger, illness, blatantly repurposed capri & historical lore.

(See the end of the chapter for more notes.)

Chapter Text

I.

There are some things in this world which large, brash men are not built to accomplish. Arthur is a warrior; he can attain stealth and speed of foot upon battlefields of any condition, to the extent that stealth is possible while armed and armored. It’s just that this is Camelot’s castle, amid outright calamity. Not a battlefield, but his home. And this sort of silence, this sort of sly speed, bordering upon a need to become simply invisible? Arthur was not built for these things.

Necessity makes him a diligent student.

It’s an entirely unsociable hour when he finally slips from his chambers. Still dressed and tightly laced from the day, he makes his way out with a rushlight burning in one hand and a linen for his mouth and nose folded in the other, just in case he should need it.

It isn’t unusual that he’s dismissed Morris early – this latest of his manservants does far more work for Camelot’s new Regent, truth be told, than her Crown Prince – but it’s gratifyingly unusual that the corridor leading to his chambers should be empty of Agravaine’s standing guard.

For all that’s changed in the year since Uther Pendragon’s death, at least George is still reliable.

The castle is quiet and eerily dark as Arthur moves down the corridor, navigating only by the weak light in his hand. To preserve candle wax, the wall sconces have all been cleared out and left empty, no longer in use unless by urgent necessity – which dictated two of Arthur’s first lessons: that an oil lamp bears good light but is easily dropped; and neither a shattered ceramic nor a puddle of oil make for effective sneaking.

There were actually two great shifts to the world the year before, one leading neatly into the other, triggering a great wealth of lessons Arthur could never have foreseen. First, between Beltane and Pentecost, there was the death of the King in battle; and then, the body barely laid to rest, what was quickly named Uther’s Wrath: the thickening of the sky above them not with cloud but with something grayer, as if some deity had stretched a hide clear across it, so that the air grew unseasonably cold and sour, and became sometimes difficult to breathe. So that the light of the very sun seemed sometimes brownish and sometimes bluish, depending upon how very much was there to hold the life-giving gifts of the gods away from the earth.

By late summer, the first harvests were all spoiled; and famine, too, came to Camelot, as well as to every kingdom within reach of it, bringing sickness and wasting and death to all manner of people of every station. There is not a single place Uther’s Wrath has not touched in the year since, that Arthur is aware of, which means that he is also aware of the many people eager to see him come of age, and to see him take his destined place upon the throne. (And it's fair, he supposes, that the people should have their prophecies and their superstitions. He only wonders if these will do more harm than good, since no crown has ever gifted a king divinity on the order of ending famine and brightening the sun.)

On the smaller scale, in the matter of his own daily life, the problems make far more sense – are man-made, caused chiefly by his uncle’s expansive and violent influence, with solutions Arthur can seek and eventually action himself, no matter the degree of difficulty. Even if he must engage in a series of treasons, great and small, in the process.

It’s impossible to spend any length of time with Morgana and Gwen during the day, so moments like this must be leveraged at every opportunity – nights free of otherwise diligently observant witnesses – despite the inconvenience. (And Arthur does maintain this distinction in his mind: between those who intentionally spy for his uncle, who is Regent for only a few months more; and those who merely witness, only passing along what they see because that is what one must do here, now, to survive.)

That was the next lesson in the matter of stealth. Early on, he was seen too often approaching the ladies’ residential wing of the castle, which inspired an intolerable line of questioning when it came to light.

“I was given to understand you’ve never been one for having your bed warmed,” Agravaine announced, over dinner. Blinking perfectly innocent eyes from his end of the table. “Or is it only that you prefer the beds of others, little bear?”

A cruel question, but like all of his uncle’s social contrivances, skillfully made soft in the delivery. Like he’d never called Arthur ‘little bear’ from the warmth of his own.

The rest of that memory is gone now, leaving only the understanding that it didn’t matter who exactly supported his uncle’s regency to the point of treason. Regardless, he could not allow himself to be seen by anyone.

Unfortunately, it can also be the case in Camelot’s castle that no amount of discretion or preparedness is enough.

Sometimes, there is nothing to be done but blunder forward, which is exactly what Arthur does as he emerges quietly from his own residential corridor only to come face to face with his uncle, whose expression twists in a rare form of consternation and surprise in the soft glow of the rushlight.

There’s a boy with him, whose name is Mordred, and whose youth is made morbidly obvious by the size of Agravaine’s hand upon his shoulder. (Mordred needs no candle and he wears no iron cuff or collar; a weak ball of light floats above the pair of them, white-blue like the moon used to be, a sure enough indicator itself that they’d expected to encounter no one else in their travels.)

“Arthur,” Agravaine says, in brusque greeting.

“Uncle.” Arthur is unable to take his eyes from Mordred. They’re both still dressed in day clothes as well, but Mordred’s lips appear purple in the poor light. From a staining wine, Arthur prays, hopelessly.

The air is awkwardly still for a breath; if none of them moves soon, Agravaine will have too much time to think.

“It’s good I’ve run into you,” Arthur says, scrambling for an excuse to be out of his chambers. “I’ve a need for Morris, but something seems to have distracted the guards. Mordred, do go and fetch him, would you?”

Mordred startles at the address, eyes big and blue and affronted under shiny curls before they narrow to slits.

“I’m not a servant.”

“Don’t be disrespectful,” Agravaine snaps, quietly. His hand tightens upon the boy’s shoulder with this gentle rebuke, which has the obvious effect of causing pain. With a sharp glance at Arthur, he adds, “We can help our young Prince, can’t we? Go on, now. And spare me a light, if you would.”

Unhappily, Mordred goes. His little ball of sorcerous light splits into two, so that one piece of it may follow him while the other remains.

“I appreciate that, uncle,” Arthur says, lowly, with a slight dip to his chin – a show of deference his father would have despised. (He’s not been alone with this man for a very long time, though, and believes he can be forgiven for that even as his palms grow damp.) “I didn’t mean any insult.”

“It’s no matter. Mordred should be happy to serve his betters.” There’s a short pause, in which Agravaine eyes him up and down, and Arthur studiously ignores the pounding of his own heart. In far more private a tone, which carries equal parts wistfulness and gentle disappointment: “I must keep reminding myself how much you’ve changed these past few years. It’s so easy to forget, when you keep no boy of your own.”

As if such a thing could be tolerable in even the smallest measure.

But this is as much like battle as like a dance or a game, and Arthur knows what part he is meant to act out here – suspects, too, that Agravaine has only guided the conversation in this direction so it will not wander toward Mordred’s flagrant and treasonous use of magic out where anyone might see it.

Eyes lowered, he can only answer with a truth. “I’ve told you I shall take no one into my bed.”

“Yes. Still such a sweet boy, aren’t you, under all that bulk? My little bear.” Agravaine sighs, reaches out; Arthur’s whole body stiffens. None of those muscles release when it is only the rushlight his uncle’s fingers run over, as if the flame is a soft head of hair to be pet. Arthur’s scalp prickles with memory. “But men have needs, and I expect you’ll understand that quite soon now. You must not fear to satisfy those needs as the gods intended, especially in times like these, when so little of the world offers comfort.”

(Never. Arthur will never.)

“Of course, uncle.”

“Well.” Agravaine slowly takes his hand back to himself. “The night is hardly spent. I’ll wish you a restful sleep, nephew.”

They part ways.

The blue-pale cast of Mordred’s sorcery follows behind Agravaine, fading at the turn of the corner.

Not a soul in Camelot now would dare now to be wasteful, and it is for this reason and this reason only that Arthur finds himself swiftly moving back toward his chambers: more than half the rushlight remains, and he’ll not stand there letting it burn for nothing while his mind spirals over painful memories, even if he personally has more dried rush at his disposal than he can ever hope to use on his own.

It’s not until he’s returned to his chambers, secure and untouched behind locked doors, that he realizes how the tension of his back and neck and shoulders has failed to release. That his breathing is tight and strained. He wishes for daylight and the satisfaction of exercising himself on the training grounds.

Even finding occupation with some correspondence he’s put off answering, it’s some time before his heart calms in his chest.

When Morris finally comes, Arthur invents the need for a sleep aid from Gaius. Might as well get use, he thinks, out of the understanding his actions will be reported back to Agravaine.

It takes the better part of a few hours to plan a new trip to the ladies’ wing, and two nights later, there are no surprises.

Arthur isn’t sure if it’s his sister’s presence that brings him so much comfort, or the fact that these chambers haven’t changed since before each of their mothers died. (Every time he settles down into a soft chair before her fire, he can recall having done so as a child with his mother, before all their lives went wrong. These are among the simplest and most pleasant memories he has.)

Morgana delivers her news from the chair to his right, already in nightclothes, as Gwen sits in its mirror to his left, close enough that she can set a soft hand upon the brocade cuff of Arthur’s heavy, close-tailored surcoat.

At the end of it, there’s a heavy sigh. “I really am – ”

“Morgana,” he cuts in, “if you are about to apologize, just… refrain.”

It would be better – or easier to find words that might comfort her, at any rate – if there were not still so many secrets among them. If he could explain that he knows about Morgause, and about the way Morgana had been tempted, long before Uther’s death, into acting against Camelot, though she’d never followed through. If he could tell her that she has no reason, truly, to apologize.

“What does this mean for us?” Gwen asks, when Morgana does not – and that’s the question, isn’t it?

The news itself is not ideal: that infighting among the Blessed – those Celts or Britons cast out by their respective peoples for the use of sorcery, together with those Akielon dragonkin still willing to leave the north, and with those lingering adherents of the Old Religion, whose priestesses live and practice their craft at the Isle of the Blessed – has significantly worsened. That they are besieged by the same unnatural weather and yet suffer no famine only compounds the matter; and worse still, just days ago, a rider came into Camelot bearing news of the rumored death of the druid Emrys at the hands of the High Priestess Nimueh.

Arthur is no stranger to Emrys as a prophetical concept, having been provided with more than one treasonous tutor over the course of his youth, and to learn in one day both that the title had been attached to a living man and that this living man was now deceased was a trying thing. To say nothing of the questions it raises: if magical people are surviving well through this time of darkness, why kill who is supposedly their most powerful sorcerer? (Was he threatening their survival? Has some shift of power occurred, as they move from winter into spring? If Arthur learned of a reason, would it even be one that he, never a magic user himself, could understand?)

I don’t know is not a phrase Arthur ever likes to use, but never has he come closer to freely admitting so. Instead, he very gently pulls away from the touch of Gwen’s hand (which, while lovely, makes him want to crawl out of his skin) and leans forward, elbows heavy on his knees.

The warmth of the hearth is reassuring against his clammy forehead.

“It means nothing,” he answers, finally. “It’s a rumor.”

“Rumors often have a grain of truth to them.”

And maybe Morgana’s right to point that out, but Arthur appreciates the huff Gwen aims in her direction all the same.

“Grain of truth or not, it’s only a rumor.” He looks at Morgana, at the heavy circles under her green eyes, at the bow of her shoulders, the dullness even of her hair under the weight she carries. “I think we should proceed until we have it confirmed from someone in Glywysing that Emrys is dead. And even if it is confirmed, I’d say we should proceed anyway. What Agravaine is doing is wrong and must be stopped. We can’t wait until I’m crowned king, and we can’t assume Emrys would help a Pendragon even if he does still live.”

Arthur won’t be crowned King until he reaches the age of majority, which is only a few months ahead for him, if Agravaine or his people don’t kill him first.

Morgana visibly hesitates, scratching nervously at the skin of one thumb with the nail of the other. She asks, very quietly, “What if I’m wrong again?”

Arthur shrugs. “That’s not a concern to me.”

“It should be.”

“There’s no reason for that,” Gwen tells her, and Arthur can easily hear in the tone that this is a well-worn discussion between them.

“Gwen’s right. Your visions are brief: only glances into the future. You can’t know everything. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ when it comes to what you see. There’s only supposition. Presumption, at best.”

“My presumption killed your father,” Morgana snaps, “and who knows how many others.”

And that’s – it’s not literally true, since Uther Pendragon was struck down on the battlefield by a dark-haired, golden-eyed young dragonlord, who still sometimes appears in Arthur’s nightmares. But Uther’s death came to pass while Morgana acted to prevent a different set of tragedies, and although there’s no way to know the cause for sure, she’s since blamed her own interference for the loss… and for everything that came after.

Arthur wishes she wouldn’t.

“It’s saved my life,” he says, resolutely. “Several times. That’s valuable. And you’ve said yourself that what’s happening out there has nothing to do with my father. The sky, this famine, these deaths – they’re of nature, not magic. There was nothing you could have done to prevent this.”

Objective truth is usually the way to settle these fears of hers, and surely enough, she sits back with a small frown instead of offering a retort, bringing thin legs up under her nightshift.

“Do you – ” She stops, restarts, and stops again. Finally, she asks, not looking into Arthur’s eyes but somewhere in the vicinity of his ribs, “How has it been with Mordred?”

The air feels a bit stale in his chest, suddenly. Not even a deep breath can clear the feeling.

“He’s asked me not to intervene.”

Morgana nods, eyes glazing a bit. Remembering a vision, maybe. She hugs her own knees, now, and Arthur recognizes these signs: the pulling in of herself, the hiding of all her weakest places. It’s a child’s instinct, one Arthur still feels himself from time to time, to become as small as possible in the face of some almighty peril. (He has no desire to know what vision is responsible for this shift, and doesn’t ask.)

“I think you should listen to him, Arthur,” she says, quietly. “Whatever he asks of you.”

Since the last attempt to liberate Mordred from Camelot left Arthur with two bloody bite wounds and several jagged lines down each forearm, gorged by sharp fingernails, he is indeed more inclined to listen. Pink lines still decorate his skin, fading more every time he looks at them, reminding Arthur of his own time at Agravaine’s side. Reminding him of how special he’d felt, how treasured, even while his soiled insides rotted with the shame of it all. Reminding him that once, he would have killed for his uncle. (He’d have fought, too, he thinks, to stay – which is why he can’t give up entirely.)

This is not a thing to be explained aloud, though, so Arthur only nods.

“Well.” Gwen clears her throat. “I have some good news, if we can bear such a thing.”

Morgana laughs in a weak huff.

“Please,” Arthur says. “Is this about your father?”

Gwen nods. “He’s accepted your offer. He can only provide in small batches, though. People notice when the forge is too active. The smoke makes them nervous.”

It is indeed good news. Relief floods Arthur’s system almost as sweetly as a wine, though he’s not unaware of the danger Tom’s decision brings with it – the danger Gwen clearly still has in mind, brow lightly furrowed over her small smile.

But this is the way rebellion works: quietly; all the dangers here at home, to be faced by anyone and not just by knights upon some far-off battlefield.

“That’s understandable,” he says. “We expected as much. Leon will have an order to pass along to him within the fortnight. Please extend our thanks as well for taking the risk.”

“He’s already said not to thank him… he doesn’t understand why so many people won’t even consider fighting back, if they still have the means.”

It’s not polite to speak ill of the dead, so none of them do – but Arthur knows that if his father’s brutality in the persecution of magic is not to blame, then the spiteful aftershocks of his death are: he’d charged Agravaine with both the regency and the final blows of the Purge, so that Arthur might grow to rule a kingdom truly cleansed of magic. Though, fatefully, little had Uther understood the depths to which Agravaine would take that charge, or the extent of Agravaine’s ambition. (Arthur’s heart starts to rush just thinking of it. There were more than a few things Uther never thought to question about his dead wife’s brother.)

He lets a few beats pass, fruitlessly striving to take deeper, steadier breaths.

“I must return to my chambers,” he says, when the trembling starts.

Morgana startles in her chair, frowning – “So soon?” – but Gwen, dearest Guinevere, shares a look with him that says she understands completely.

“We’ll see you the day after tomorrow, sire.”

Which shall be a feast day, or what remains of feast days in these darker times. A show of power and strength, such as it lingers, with the added benefit of feeding people who starve. With any luck, there will be no ill-fated marriage proposals at this one… for himself or for Morgana.

When Arthur doesn’t move right away, Gwen rises to prepare another rush for him, lighting it at the hearth. She slips the iron nip carefully into his hands with a sad smile.

“Good night,” Morgana says, staring deeply, with unfocused eyes, into that flame.

Gwen watches her with concern, but since the vision might as easily end in one hour as in one minute, Arthur still takes his leave.

These may be very small steps, he tells himself as he walks carefully back to his chambers, but each night like this one moves them forward. Each ally gained. Each prisoner freed. Small but impactful; quiet but enduring.

This is the way he will take back his kingdom. This is the way he will lead his people out of the many darknesses which have descended upon them.

Merlin awakes to the most visceral agony he has ever experienced in his life, centered at the point of an icy branding about his neck, hard and tight along the skin. He can barely draw breath to scream.

A hand slams down over his mouth.

“Take it off,” someone hisses in Brythonic – the language of the druids. “You’ll kill him like that.”

The agony recedes immediately. Merlin is blind in the lightless room, shaking and sweating and struggling for breath through his nose as waves of his own magic bury him. No sooner does he flail against unwelcome touch than it all begins afresh – from the point of his right wrist this time, wrapped where he once felt the lick of Akielon dragonfire and still bears the scarring. The pain is less, though, here. Manageable.

He begins to understand that his magic is being stripped away from him.

“Please be calm, Emrys,” comes that same whisper from the left side of his mattress, leaking frustration, as if Merlin is in the wrong here.

The druid lifts his hand, suddenly, to let Merlin speak.

“What are– you’re killing my magic,” he gasps, reaching desperately for their language over his own, not even capable of fear or horror now. There is only the single-minded drive to escape, to not let this advance any farther; but the cuff is doing strong, steady work.

Merlin feels heavy. Dizzy. He can’t feel his face or his fingers or his toes.

“We’re not killing anything,” the other man assures him, also in a whisper. “We’re saving your life.”

There’s no sense in that, but Merlin isn’t in a place for sense. He went to sleep in the spare bed of his mother’s home at the Isle, and if he’s waking in agony then it means– it means–

“Mother,” he slurs out, in his own tongue, shortly giving way to a guttural, wordless groan that pushes up from his belly as a second cuff is locked around his other wrist. He can’t control his mouth, can’t make his lips form the right shapes. His whole body seizes, back arching, limbs cramping.

“Your mother is safe, Emrys,” the first druid tells him, setting a cool hand to his forehead – at least, that’s what Merlin thinks he says, over the pounding of his heart and blood in his ears. “Only sleeping. She’ll wake unharmed. Listen to me, now. Listen well.”

And the circumstances are explained quickly, concisely, delivered in a series of blunt facts that don’t feel even half real: that Merlin has been sold by the High Priestesses to the near King Cenred; that Merlin’s disappearance is meant to look like an act of aggression by some external party, because that is the simplest way for Morgause and Nimueh to eliminate the threat of Emry’s influence upon the Blessed as they prepare for the war Merlin refuses to support; and that the druids here now have been the architects of the plan involving Cenred, but would allow no others to touch Merlin, with their deepest apologies.

“The Priestesses preferred to destroy you outright. We couldn’t stand for that,” the other druid says. “We’ve seen ahead, and at least this way, you’ll soon be united with the Once and Future King. Destiny is not lost to either of you, no matter how dire things may seem in this time of dark and dying things.”

If Merlin were in a place to form speech, what left his mouth might have been violently explicit in nature. (He lived part of his life in Ealdor, which persisted through all the heaviest marks of the Roman-Gallic invasion, and of the rise and fall of Vere; he knows what Cenred does – what Uther did; what Agravaine and Arthur and many other nobles also still do in those lands – to users of magic.)

As it is, he can only pant into the rolling crest of what feels like a wave of death itself.

The sun will brighten, Emrys, and the skies will clear, he hears in his mind. Mother Goddess will make the way for you.

“I think he’s ready,” the first druid says to the other. “Try it again.”

A cold, thin band of iron is snapped in place then around Merlin’s neck, and it isn’t like what woke him at all.

It’s worse.

It may well be that the days are sepia-dim and the air often sour, but Camelot’s need for fighting men has not waned, and so Arthur persists in training them.

No kingdom can war effectively while famine persists, but what hovers there in counterbalance is the threat of what happens when the needs of the people become too great – when they have too little and suffer too much. History carries this lesson: the Roman-conquered Gauls were quick to invade and shatter what was once the kingdom of Albion, leaving much of their own culture behind them when eventually they in turn fell to invasion; the languages Arthur now speaks are testament enough to the ways of the warring world, and he refuses to stand next in that line of ill-fated kings. Camelot must stand ready to defend herself against bandits and raiders, yes, but most especially she must resist the knights of those neighboring kingdoms which might yet make war out of desperation.

The morning after his talk with Morgana and Gwen, training takes a turn. The winds are too still and the air too poor in quality, even through a mask of fabric. The men who can’t breathe grow too easily dizzy; the men who haven’t eaten enough are too lethargic.

Arthur’s at about wits’ end when Gwen appears at the end of the training field, long strips of linen fixed over her nose and mouth.

“What is it?” He takes care to look agitated at the interruption, even if he can’t bring himself to sound outright intolerant of it. The knights – Agravaine’s knights in particular – observe with interest.

Angling herself away from their audience, Gwen answers quickly. “It’s Morgana. Cenred has sent some sort of gift. She’s making too much trouble.”

Since Morgana and trouble have long been bedfellows, Arthur assumes the gift is something dire. His sigh gutters out on a hacking cough.

As if having to hide her visions and magic is not enough, Morgana has also had to contend with Agravaine’s excessive attention. (Neither carnal nor excessively inappropriate, fortunately – Mordred’s presence is a continually sobering reminder of the cause for that – but since the matter of Morgana’s parentage came to light, she’s been of rather transparent interest. If Arthur is killed, Morgana would be the last living Pendragon; and who would protest, amid the worst famine in recent memory, if the sitting Regent then crowned himself King and took her for his Queen? The fact that Morgana herself would oppose him is, unfortunately, beside the point.)

Agravaine’s obvious favor usually protects her, but if Gwen has come…

“The gift,” Arthur whispers, doing his best to look unbothered, “is it pets? Sorcerers?”

Not that the keeping of pets in the old Veretian tradition is not itself sometimes appalling, but Arthur doesn’t think Morgana would risk her own safety over men and women who would at least agree to the length and terms of their contracts. It must be sorcerers, he thinks – sorcerers who will be made into slaves.

“Sorcerers. At least seven, and it seems only half of them are speaking,” Gwen answers, which means, at best, that half won’t understand either common Latin or Veretian, and won’t know what’s happening around them. “She’s delaying the presentation, but she can only do so much.”

Arthur nods. “Run ahead for me and I’ll follow directly. If they won’t allow for delay, tell the Warden I will exercise my Right of Firsts. Don’t let Agravaine see you.”

A complicated expression crosses Gwen’s face, but she only nods, and runs ahead as ordered. Arthur has never owned a slave. His every encounter with slavery in the past was either to hear it denounced or, as a knight, to condemn and eliminate its practice. Uther never permitted it, though it wasn’t unheard of under the Roman Gauls or even still, outside of former Vere.

Without question, in Arthur’s opinion, the reintroduction of penal slavery to Camelot is the most reprehensible change Agravaine has brought about in the last year. Those found guilty of using magic now face an impossible choice: to lose their lives for it, or to keep their lives but lose their freedom. Agravaine didn’t even have to push very hard to implement his new scheme, speaking convincingly and with haughty confidence to councilors and subjects who were desperate after a hard winter, so that now it is phrased like this: that magic users are lucky to have this option, to be useful to their neighbors instead of dying a useless death; that Agravaine is generous to have offered it.

Unprecedented suffering made people nervous and fearful, and the rumors about magic users – most prominent among these, that they prospered while the rest of the world wasted away – killed off almost the last of all opposition. The general attitude, as Arthur understands it, is that people are too concerned with managing their own perils to bother about anyone else’s. This is why Arthur needs Tom’s work at the forge, now more than ever. This is why they must smuggle as many prisoners from Camelot’s dungeons as possible.

This is also why the Crown Prince claiming his Right of Firsts is not a good idea, and he hopes he hasn’t spoken too carelessly in his haste to protect Morgana.

Arthur ends his training session quickly, without dramatics, which he’s discovered is important when more than half the men are now deep within his uncle’s pockets. Only Leon lingers, with Lancelot and Gwaine not far behind. Three of his most reliable men.

“Sire?”

“I may need you later,” is all Arthur can say. He goes directly to where he’s needed from there, mail and all.

Most of the castle’s dungeons are subterranean, but there have always been two large, open chambers left empty at where the grading of the land slopes downward enough to allow direct access from outdoors. In Uther’s time, these were considered weaknesses to be disguised and defended. Now, they are used for the detaining, crude bathing, dressing, staging, and formal presenting of slaves.

By the time Arthur arrives, Morgana is nowhere to be seen; neither is Gwen. That’s one piece of trouble to be revisited.

The more immediate trouble is this: that Arthur’s eyes immediately fall to the line of prisoners kneeling naked at the center of the room, and that his father’s killer is among them.

Balinor’s son, whose name Arthur never learned.

Balinor’s son.

And he’s lost for a moment.

For just this moment, he’s eight years old again and his father is away at war, so long that his uncle has come to watch over him. He’s eight years old and has stumbled bleeding from his uncle’s bed, and Balinor is there in the hall to stop him. To see him. To take him to Gaius.

“What are you doing there, boy?”

Arthur stopped short; held himself perfectly still, like a statue. His heart pounded so heavily it seemed to shake his entire frame. He couldn’t see – but that must be Balinor, by the foreign sound and the fuzzy shape of him.

“Whatever I like,” Arthur said, chin high. Numb. “This is my uncle’s corridor. What are you doing here, Dragonlord?”

“I was invited,” Balinor answered, shifting one hand to move something shiny under his long woolen chiton. “Don’t you remember my name?”

“Your people are fighting against my father. Why should I use your name?”

That was only half true – even Arthur, at his age, knew not all dragonkin were at war – but saying something vicious felt right. Felt like venting a little of the sharply aching pressures building in his chest and behind his eyes and back between his legs.

Balinor drew closer. “Arthur. Why are you crying?”

Arthur’s hands flew up to his face, and sure enough, the cheeks were wet.

“I’m not,” he insisted, wiping frantically at himself. “I’m not.”

But each denial came out thicker and thicker, and the next thing he knew, he was sobbing silent rasps into Balinor’s warm shoulder, mouth open and wet and ugly as the dragonlord took him up and carried him away.

The way some people tell the story, Uther’s purge was an immediate shift. An irrational response to his wife’s death. Arthur knows that’s not the case.

Arthur knows it was the secret he failed to keep. The thing Balinor learned that Agravaine could not stand to let be known – that Agravaine poured poison after poison into Uther’s ear to defend himself against, piling evil after evil atop magic and the death of the Queen, until Balinor and his people were chased entirely from Camelot on pain of death.

What Arthur also hates to remember is this: that just moments before his own death last year, Uther stuck his sharpest blade between Balinor’s ribs.

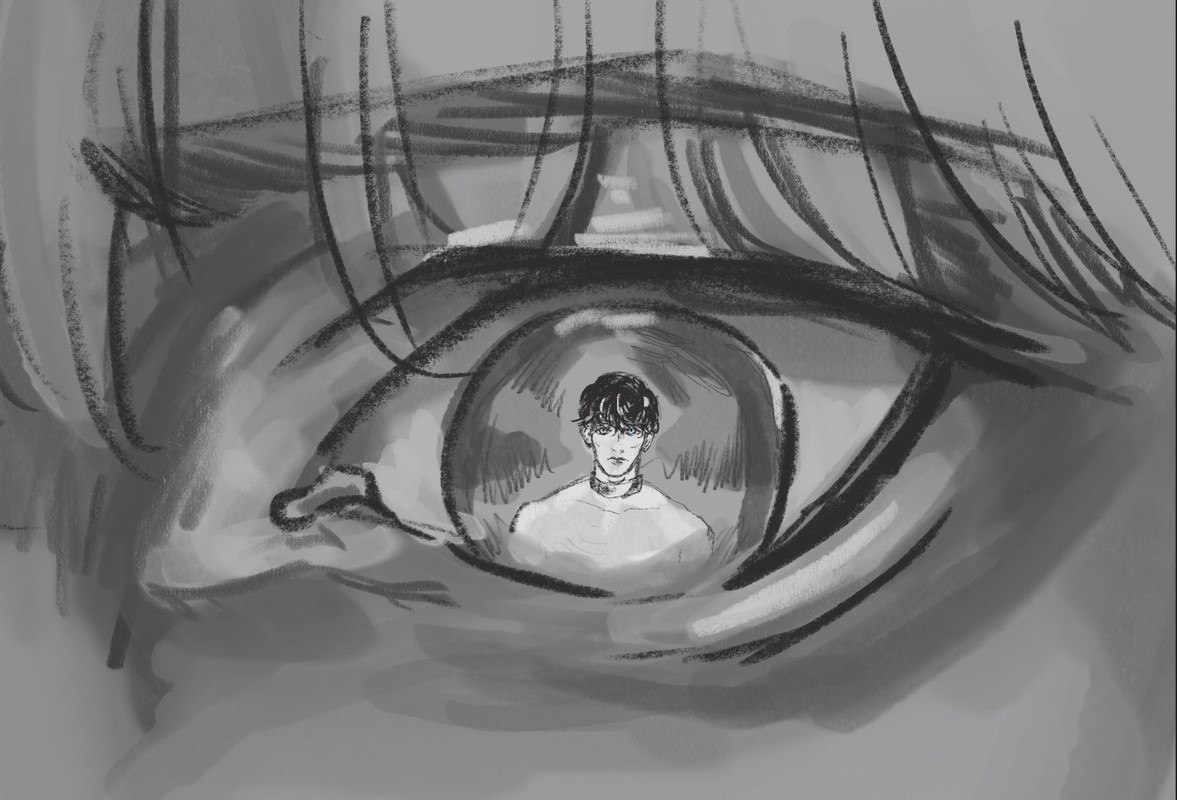

It was over in a moment. Arthur hadn’t even raised horrified eyes from the wound before the boy was there screaming for his father in one of the ancient tongues, eyes shining golden and devastated – before he struck Uther down, and Arthur with him, with a blast of magic. Arthur survived, of course, though scarred across his torso and the tops of his thighs… and now Balinor’s son is here kneeling at the center of a line of gaunt, bone-thin young men, all of whom have been bound with a collar and cuffs of cold iron. Enslaved. Stripped of power as easily as of clothes.

The air has been perfumed, no doubt to cover the fact that none of them has been washed. Arthur can barely stand to breathe it, even at this distance, looking in from the corridor.

The boy hasn’t noticed him. Neither has Agravaine, nor the three councilors with him, only one of which, Sir Ector, had also been his father’s man. Mordred, who usually sticks close by the Regent, is thankfully nowhere to be seen.

With a fortifying breath, Arthur straightens his back and raises his chin. He walks confidently into the room.

“Arthur, welcome,” Agravaine says, benevolently enough. “We’ve heard you’re to claim your Right. It’s about time, I suppose. Though really, you could have washed first.”

Deep, deep breaths. Arthur knows the rules of this game well enough; there’s no point in rising to meet each little jab. Indeed, he must strive to land a few of his own.

“Yes, well. Training is harder work when we accept knights of this caliber. I hear Cenred has sent a gift?”

“Several,” Agravaine replies, far more curtly.

“And what does he gain in exchange?”

“Nothing, nephew.” His uncle aims a barbed smile in his direction, a patronizing thing, folding arms calmly over his robed chest. “Don’t you understand the concept of a gift?

Instead of acknowledging that, Arthur wanders over to the line of kneeling sorcerers – not too close, but enough that some risk to raise their eyes to meet his. Balinor’s son is one of those, neutral-faced under thick, dirty hair.

If he recognizes Arthur, there’s no indication of it. His natural eyes are blue, like Arthur’s, but a bit lighter. Warmer. Clear like a summer sky. They will never shine gold as long as he wears the iron, and that seems like a tragedy. (Arthur feels no shame to admit to himself an objective truth: that whether blue-eyed or golden-eyed, whether soiled by the trials of warfare or the indignities of slavery, this boy is the most beautiful he’s ever seen.)

Agravaine notices his preoccupation and, for a moment, Arthur is fiercely glad he deferred so readily the other night. Something tells him that this is about to become the most challenge he’s offered his uncle in a very long time.

“The two on the far end look most suited for your Right. The rest have a bit of a feral nature about them, I fear. Not suited for the hand of a prince.”

Arthur doesn’t move from where he stands.

“This one bears an Akielon’s mark,” he counters, nodding down at the boy, who turns his eyes quickly back to the stone floor. No amount of dirt could hide the sigil at his neck. “There will be no one more suitable for me than a dragonlord, uncle. Don’t you agree?”

Slightly light-headed, it occurs to him that he doesn’t need Agravaine to agree with him. The Right of Firsts says he can take any pet or slave for any length of time, regardless of their status or any contractual agreement. (Technically, it says that any ruler of Camelot may do so; but Agravaine had written that into law when he believed himself to be the only ruler who would ever take advantage of it.)

“I’ll have him,” Arthur says, decisively.

A heavy pause.

“You?” And it’s impressive, really, how politely disdainful Agravaine makes this question sound.

“I’m Camelot’s Prince.” Arthur gives a well-practiced, bordering upon insouciant shrug. “He’s a dragonlord. Wouldn’t you agree I deserve the best?”

“You haven’t yet taken a slave. You argued against the practice.”

Arthur nods. “And it’s been months now since it’s begun. What better time to start?”

The councilors shift nervously in the face of this challenge. It’s clear enough that they don’t know what their role is: whether they should speak against their Prince to support their Regent, or whether they should stay silent until informed of the opinion they should have. Ultimately, none of them speak. They let Agravaine have the span of silence he spends surveying Arthur.

Fortunately, Arthur is not incapable of withstanding his uncle’s attention.

“I’d thought to take him for myself,” Agravaine says, at length.

“Oh?” Arthur makes himself placid. Calm. A mountain unmoved by any force of nature. “I’d have thought this one quite too old for your taste.”

The boy is obviously no older than sixteen; this is the closest Arthur has ever come to making any sort of accusation aloud and in the hearing of others. His heart races in his ears. He must breathe through his nose, grounding himself through the rancid scent of unwashed bodies, to keep steady.

There’s some more nervous shuffling among the councilors, but no outrage – which tells Arthur that these men are either uncomfortably accepting of Agravaine’s inclinations or unwilling to recognize them for what they are. Agravaine himself only spares Arthur a shallow smile which spreads wide under baleful eyes.

“Well, by all means, take him on. Your appetites run rare enough that I never mind indulging them... just be sure not to abuse him. A dragonlord killed your father; there would be no excuse to take that out upon the boy.”

The implications aren’t important, Arthur tells himself. What’s important is that he’s won this round. Balinor’s son is safe with him. (Or, at the very least, as safe as it can be for a sorcerer in Camelot. As safe as anything can be for anyone, these days.)

“Stand,” he says to the boy, who only looks at him blankly.

Arthur frowns. He knows that dragonkin speak their own language, but Balinor never stumbled with Arthur’s, and it doesn’t make sense for his son not to have any grasp of it. If language is a barrier here, this will be excessively difficult.

“Stand,” he tries again, this time in common Latin; then again in Brythonic, and a last time in his best estimate of the draconic Akielon, to no response but the slightest of frowns.

He asks, circling back to his own Veretian, “Do you truly not understand me?”

Agravaine gives an impatient tut, steps closer – close enough that a few of the other boys turn their eyes obediently back to the ground – and says, silk-smooth, “He’ll understand the whip perfectly well.”

There’s no disguising the way the boy’s eyes dart to Agravaine, wide and outraged at that, which betrays his understanding. His defiance.

“Look at me,” Arthur says, in the hard voice he uses with his knights. This time, the boy obeys. Maintaining eye contact with his father’s killer is possibly the most trying thing Arthur has had to do since all of this started. “You will be whipped if you disobey me. You will not be whipped if you follow my direction. That’s a very clear distinction, and I assure you, there will be no exceptions. I am a man of my word. Now – stand.”

The boy glances once between Agravaine and Arthur. Slowly, he stands.

Arthur does not look at the nakedness; he looks at Agravaine, who is staring hard already back with beady, unhappy eyes over a false smile.

“I thank you, uncle, for allowing the interruption.” To the boy, Arthur says, “Come with me.”

There’s nothing he can do for the others, he tells himself. Not yet. Not when he’s made such a nuisance of himself already.

“Take a few of my men with you,” Agravaine calls as Arthur leads them out of the room. “It would hardly do to ruin any part of Cenred’s gift the day we receive it.”

It’s a short matter of procuring a spare linen for Balinor’s son, to grant him some dignity as they trek through the castle – though Arthur supposes, if he remembers correctly, that if the boy was raised in the Akielon tradition, nakedness will matter as little to him as it does very much matter to Arthur.

Flanked by two guards that Arthur half expects will attack them outright for what he’s done, the walk to Arthur’s chambers is silent and quick, which is fortunate.

The Prince is tired, and hungry, and has no idea what he will do with this king-killer now that he’s claimed him.

Waking up came in stages for Merlin, the first time.

To begin with, there was the shock of being alive: the realization that he still had a body and could feel every aching piece of it, including a stomach wracked with hunger and a throat so dry he couldn’t even swallow. Next, the numb understanding of the loss of his magic, all the roots of it dug out of him, unlike anything he’d ever known before. (It went beyond physical feeling, this loss; he was simply no longer himself.) And last, the burden of having eyes to open, and sight to take in his surroundings: outdoors; himself in a cart large enough for his own body laid flat alongside six other men who had room only to sit; and an array of mounted knights cloaked in the colors of Cenred’s kingdom.

“Look who’s decided to join us,” one of the other prisoners said, in common Latin – to one or two unenthusiastic scoffs, but to far more blank faces.

Merlin pretended not to understand him.

“Where are we?”

He used his own tongue to ask, having decided immediately that a little deception in the area of language could only benefit him. More blank faces met that question; either no one understood Akielon, or no one could give him an answer.

One of the knights brought his horse alongside the cart, then, so as to kick at it. Merlin felt the impact deeply in his throbbing skull.

“Shut up,” the knight snapped in Veretian, which was telling for a knight from Essetir – though there was no time to pick that information apart, because, seeing Merlin awake, the knight struck him heavily enough to remedy that condition entirely.

Some part of his reputation, apparently, had preceded him.

Waking the second time was only slightly less painful, and came with the fortuitous appearance of knights cloaked in red, all evidence of Cenred’s men gone. At least the druids hadn’t been overly long-sighted, for once: he opened his eyes indoors, now naked in what looked like a bathing chamber, surrounded by cowed, emaciated bodies whose faces were familiar from the cart.

The best thing about that room was the water he was given to drink, which he sipped at slowly, so as not to lose it.

Merlin knows most of the history of Albion’s demise. In that stone chamber alone he could see the tells of it, particularly in how the small, shallow baths were maintained. In the strong Veretian artisanry which was descendent of older, more violent times. (Merlin is admittedly not the finest historian – there are steps and whole centuries, he remembers his father telling him, between the Roman Gauls invading and the advent of Vere and Veretian customs, and shortly later, the breaking of Albion entirely into all the smaller kingdoms – but in fairness, he has had only the verbal histories to rely upon, and the stories his father told him of the court at Camelot.)

And this certainly is Camelot, where he finds himself. Cenred has apparently tossed him directly into slavery, which feels profoundly ironic, as Merlin’s stance on the response to this practice is one of the things upon which Morgause and Nimueh disagreed with him the most.

But even after the debacle of being claimed by Camelot’s Prince – who seems not to recognize Merlin as the killer of the late king – and as he quietly limps after Arthur Pendragon across his castle, flanked by guards, Merlin still doesn’t think more bloodshed is the answer.

Or, he thinks he doesn’t. He’s rather distracted now by the notion that the slavery here could be in any way sexual, as the Regent implied downstairs. (It’s the concept of a pet, isn’t it, that bears the connotation of sexual servitude here in Camelot? For a slave to serve that purpose is quite out of line with what Merlin thinks he understands of their culture, otherwise confirmed by the way the Prince immediately procured a linen for Merlin’s nakedness, which bothered Merlin not at all. Surely he won’t be made to warm anyone’s bed?)

Also immediately distracting is clear evidence of the way the false winter’s famine has also hit Camelot, conflicting with reports that the Regent now forces his sorcerer-slaves to use their magic for his own benefit. That, at least, seems to be an unfounded charge.

Up flights of stairs and down several poorly-lit corridors, they finally come to what looks like a short residential wing, softened with colorful tapestries upon the walls, the color and detail of a wealth Merlin has never seen with his own eyes. The Prince leaves his guards at one end of this corridor and wordlessly bids Merlin to follow. As they approach a set of broad double-doors, here is another distraction, waiting with a cold demeanor: a curly-haired, blue-eyed young druid, who regards Merlin with the sort of distaste and distrust most children don’t know how to wield.

He's dressed finely, this boy, in the style of Camelot’s Veretian nobility, and does not bear the indicators of hunger as severely as others they’ve passed in these halls. Though there is a druidic mark on his neck, indicating magic, he wears no iron. Merlin doesn’t immediately understand how this is possible. Short of slavery, there are not many reasons for a druid in the possession of magic to be a valued guest within this castle.

The lack of iron worries Merlin, in fact, far more than he is worried for himself.

What are you doing here? He tries to ask, mind to mind in the druids’ tongue, only to recall that his magic has been cut away from him.

“Mordred,” the Prince greets, warily – too warily. Merlin doesn’t understand what passes between them, why the child’s eyes look so angry and so betrayed as they glance between Arthur Pendragon and his new slave.

“You’re a liar,” Mordred spits back at him. “You’re a liar and a hypocrite. Never speak to me again.”

He seethes vitriol in nearly palpable waves; Merlin finds his breath stalling in his chest just to be standing here in the line of fire.

When neither defense nor explanation comes, the child turns and runs in the other direction, as if for his very life.

The Prince doesn’t look at Merlin as the echoes of pounding feet fade away. He turns back to glance far behind them and seems relieved that the guards linger back at the end of the hall, backs turned, seemingly unaware of what just happened.

“Come,” he says, and pushes into his chambers.

These are large, Merlin notes, and divided into two parts: a sleeping chamber at the rear, containing a bed and beautiful windows and all the royal trimmings, from the little Merlin can see of it from here; and at the front, a chamber meant for business and socializing and the like, separated by a partial wall of delicate arches and columns. There’s a table and chairs here, a hearth with a tame fire lit and another set of softer chairs before it, a desk at the wall ahead, and a sideboard under even more beautiful windows.

There was never glass for windows at the Isle. Before the false winter, Merlin would have preferred that, to be always open to nature and her gifts, as was the old Akielon way. Now, though, he sees the benefit in a barrier between a home and the outside world. (That they are handsome helps, too. He adores how the colors in each pane catch even the low light; how the iron-wrought shapes please the eye. They must be absolutely stunning in direct sunlight. These must be the most Veretian thing Merlin has ever seen, now; more so even than the tapestries.)

On his left stands a dressing screen, which hides what Merlin is sure are the usual unmentionables; and before that, a decently sized wooden tub, into which two servants are currently dumping a few last buckets of lightly steaming water.

“My lord,” greets one of them, a young man with brown hair and a pinched, unkind face. When he turns and spots Merlin, his eyes go wide.

“Morris, this is – ” the Prince pauses, frowning. Turns his keen eyes to Merlin and asks, “What’s your name?”

There’s no reason, really, to withhold it. Not the real one, at any rate.

“Merlin.”

There’s an awkward pause at that. The Prince sighs, deeply, and briefly digs the knuckles of one hand into his left eye. This stance makes the hardness of him, of his sweaty grit, the worn mail, the world-weary strength, seem a bit like an illusion. Like there might be something else underneath all that.

Morris scowls at Merlin, who isn’t quite sure what he’s done to deserve it, aside from arrive dirty and in the obvious possession of magic, however useless.

“This is Merlin,” the Prince says. “He is now a part of my household. Ensure the Steward is aware. I’ll be determining Merlin’s duties myself but will consider any recommendations he’d like to make in the meantime.”

“Yes, my lord,” Morris says, staring at Merlin as he pointedly emphasizes the honorific.

Ah, Merlin thinks. Yes. They do that here.

He’s not sure he’ll be able to refer to the son of Uther Pendragon by anything but his title, and, perhaps a bit petulantly, decides that adopting the Veretian idea of cordiality is not one of his priorities.

The Prince gives Merlin a cold once-over, then adds, “Any requests the Steward has should bear in mind that Merlin is not accustomed to having to conduct himself around nobility. My preference is to keep him off the whipping post for now.”

It takes Merlin a moment to confirm that he has not misheard or misunderstood this – but no, the Prince spoke clearly. It’s a testament to Merlin’s exhaustion that he can’t be bothered to wonder more about it. Camelot’s Prince has every reason, after all, to bear animosity toward a dragonlord.

“Have a meal brought up for him,” the Prince goes on to say. “Find him some clothes. And arrange for the antechamber to be made up for his quarters; I am not unaware of his parentage and I will keep him close until I can be sure no one will harm him. Let this be known, too: that Merlin is my property now, and I expect that he will be attended to with the same care and diligence a servant might reserve for anything else that belongs to me.”

“Y– yes, my lord.”

It’s interesting that these directions don’t land as easily as the others.

“That will be all, Morris,” the Prince finishes, pointedly.

The servants leave without another word; the second was never even addressed directly.

Merlin is not put off by his circumstances, or by any of this royal posturing, or by the harsh judgement of a servant. He waits only for the doors to close behind them to stand tall and announce firmly, in his best Veretian:

“I am neither a slave nor a whore. There will be no whipping or bedwarming. I will do whatever you ask, within reason, as long as you request it respectfully. Those are my terms for remaining here without a fight.”

And the Prince lets him say it.

The Prince lets him say it, wandering in closer, calmly, as he speaks, until the last word leaves his mouth – only to strike Merlin with an open hand, hard across the face. Hard enough that Merlin’s neck cracks at the twist of it; hard enough that the world shakes, that his stomach churns, that his breath comes in short gasps. His eyes water, instinctively. Pain doesn’t even have a chance to set in before the Prince is gripping Merlin tight by his dirty hair, straightening his head and pulling it back, so their eyes can meet. Merlin has no control over the sounds this pushes out of his throat.

“I don’t care how you speak to me when we’re alone,” the Prince says, cool to the point of indifference, “but if you were to speak like that before Agravaine, he’d beat you to within an inch of your life with as little hesitation as I’ve just shown you, and I wouldn’t be able to stop him. If you were to speak like that to any noble aside from myself or the Lady Morgana, you’d have ten lashes by the whip at the very least – so it’s for the best, I think, if you don’t get into the habit of speaking like that at all.” Slowly, he releases him and steps back – very slowly, frame all tense lines and stiff muscle. “I don’t know what it’s like where you come from, Merlin, but there are hard lessons ahead of you if you can’t understand the part you must play here to survive. Excuse me.”

It’s the smoothest shift from callous to cordial that Merlin’s ever seen, but somehow, not an incongruous one; not even the mention of Morgana can distract from it.

The Prince stalks then straight past the full tub to behind the changing screen, from where Merlin promptly hears a shuffle, a heavy drop, and the unmistakable sound of a thick, wet heave.

Any other prisoner might have taken this opportunity to try the doors, to flee, or to find a weapon. That might have been the smart thing to do, but for the first time in days, Merlin takes the opportunity to think, to breathe, and to slow his racing heart. To make a choice for himself, assessing his meagre options.

He chooses to stand and listen as Arthur Pendragon is violently sick into what must be his own chamber pot.

At length, when silence has fallen but no movement follows, Merlin chances to ask, sounding waspish even to himself, “Have you died over there?”

“Unfortunately not,” the Prince replies, flatly, from behind the screen.

Merlin snorts. In Akielon, he mutters, “Would you like some assistance with that?”

Unexpectedly, there’s a thick huff of a laugh, and then, in passable Akielon: “Have you forgotten already that I speak your language, dragonlord?”

And truthfully, Merlin hadn’t assumed that a simple command to a slave conveyed any command of the language itself. He finds his cheeks flushing more in embarrassment at being caught out than in fear of any repercussion.

“And no,” the Prince adds, in Veretian again. “No assistance needed, unless you’d like to do Agravaine a very special favor.”

A pinch of reality sobers the mood. Merlin draws the linen even tighter about himself, ignoring how his cheek and skull throb. He’s known for several months now that the subject of the Pendragons’ future in Camelot has become a tense one, but he’d never have imagined that the Regent’s desire for the throne – and what he might do to secure it – would become something the Prince might mention so flippantly.

He doesn’t quite know what to do with this man’s unflinchingly candid nature.

“Are you… ill?” Merlin asks, reluctantly, after another few breaths. He’s heard lately of starvation sickness, plague sickness, breathing sickness; and then there’s the potential for the non-natural sicknesses. Too many options to consider.

“Are you actually an idiot,” the Prince shoots back, hoarsely, “or should I give you the benefit of the doubt?”

“No need to be a prat about it. Just wondering if I ought to call for your physician. Or– or is he not to be trusted?”

There’s another thick laugh, which pleases Merlin to hear, and a low grunt before another retching sound, which, confusingly, does not please him at all.

“No need for that,” Arthur croaks, when he’s finished. “And Gaius is a decent man. He does what he must do to survive Agravaine, so don’t be overly trusting. But you can go to him for anything you need while you’re here. Which I imagine will be very much, if that mouth of yours is any indication.”

And Merlin isn’t sure if that sounds like a threat or not, but any chance to press on that front is cut off by the swinging open of the chamber doors, through which stumbles someone unfortunately and surprisingly recognizable.

“Oh,” Guinevere gasps, stopping short, one surprised hand flying to her throat – and Merlin is sure he must look no different, eyes wide upon her and what she carries: a tray holding a cup, a small bowl of what looks like pottage, and a half-palm-sized portion of dark, nutty bread.

Merlin has not tasted bread for more than a month, but he knows that outside the Isle, many have not had it since long before winter, when harvests across all the lands were fouled and died. To see it here at the castle in spring should not be a surprise, maybe, given the wealth of nobility, but he’s stricken by it anyway, his mouth watering even as his stomach cramps at the smell.

Then, of course, there is Guinevere herself.

She looks different to the last time Merlin saw her, but perhaps that is only because this time, she is not a prisoner. She’s lost some weight, though not so much yet that her bones show with any unhealthy depth. Her soft yellow dress highlights the far healthier glow of her dark skin. The scar at her cheek has reduced to something almost unnoticeable. She was already beautiful, of course, but that’s all the more obvious now, with the signs of her confinement by Morgause all but gone.

“Go,” Merlin whispered. The girl stared with wide eyes as his magic cleared the way for her, heavy boulders crumbling to dust without a sound, leaving nothing more than sand for her to wade through. The sun shone brightly at the end of the cavern’s tunnel. So close.

“But – ”

From deeper within, Morgause’s men were rallying. A horn sounded somewhere nearby.

“Your freedom is reward enough for me, if that’s your concern,” Merlin said, shoving her forward. “Go, now. Please. And don’t let the High Priestesses put you in this position again. That’s all I would ask of you in return.”

Of course, he couldn’t have known who she was when he freed her. That she was Morgana’s servant; that Morgana wasn’t quite as on board with Morgause’s agenda as it had always appeared she was. At the time, he only knew that she’d been held against her will and unfairly treated.

“Good day,” Merlin cautions to offer, unsure how to proceed. Very aware that he smells; that he’s dirty, and shackled in cold iron, and clearly out of his depth. Such a reversal of roles as to be comedic, in any other circumstance.

“Good day,” she parrots back. Staring. Staring especially at where his face is now swollen and hot with the impact of Arthur’s hand.

He can’t blame her. Throughout her short captivity, they’d hardly spoken at all. Hardly acknowledged their respective positions on opposite sides of the war… and they certainly hadn’t exchanged names while they were at it. He only learned hers later, because of Morgana.

And the Prince did just mention Morgana, so really, Merlin should have considered that this might happen.

“Gwen?”

The croaking of that royal voice takes on something relieved in its undertone, something almost soft, and Guinevere shakes back into action, first setting her tray on the table to make sure the doors are bolted, and then studiously ignoring Merlin to disappear behind the changing screen as well.

Because Merlin is not an idiot by any means, he listens carefully.

“You shouldn’t be back so soon,” the Prince mutters, in a voice thick enough to tell Merlin he’s not quite finished back there. “How is Morgana?”

“Confined to her chambers, but otherwise well,” she replies, quietly. “And Morris sent me, this time. I think he’s trying to make a point, though I’m struggling to see what it is. I’m also meant to get a look at – Merlin, is it? – since you didn’t leave him to wash with the others. My brother’s cast-offs will fit him, I think. And I can have someone ready the antechamber for him this afternoon.” A pause, and then, softly: “Are you well?”

“I’m well enough.” There’s a brief pause, and when the Prince goes on, he does so far more quietly, and in common Latin. “The last thing I need is another pair of eyes in these chambers, but I don’t think there’s anywhere safer to keep him.”

“Safer?” Guinevere’s confusion is palpable even unseen. The way she stumbles over her words, struggling to follow the Prince’s lead, is what tells Merlin this language shift is not a casual one.

“Agravaine wanted him. I asserted my Right anyway. That’s not the sort of challenge my uncle will leave unanswered.”

The next few moments are heavy with the obvious abnormality of an outsider’s presence. They continue to speak, lower still, so that Merlin can’t make out the words at all. There’s a light shuffle of fabrics, too, and then the sound of a pot shifting across stone. A spare burp and hiccup. Another round of heaving… dry, this time.

Finally, Guinevere reappears from behind the screen. She puts on a determined smile that largely belies the worry still shining in her eyes.

“Merlin, it’s a pleasure to meet you,” she says, in Veretian again, and very politely, as if they’ve never met. “My name is Guinevere, but everyone here calls me Gwen. You may do so as well when we’re alone, but please understand that as a– I mean, please understand you’ll have some freedoms that traditional prisoners do not, but outside of this room, you ought not to be too familiar with anyone of any position, myself included. For your safety, while we– while you’re here, that is – you ought to use honorifics for nobility, and titles for more highly-ranked commoners like the Steward or the Marshal. And full names for everyone else.”

Merlin nods, not wanting to appear like he doesn’t value this input. “Understood. Thank you, Gwen.”

Nervously, she swipes her palms down the side of her skirt.

“Have you served anywhere before? In any capacity?”

Merlin shakes his head.

“Right. Well. You must know that with the state of things, there are rules and rations in effect. The kitchens will mind your food rations for you daily, as long as you remain in the Prince’s service, and the Steward will mete out wood for his hearth only once every sennight, so use it sparingly, if that falls within your duties here. No candles or lamps should be lit unless absolutely necessary, day or night. There are rushlights now if you need to move about anywhere at night, but be sure to save them if you don’t burn the whole in one use. Prince Arthur will determine your duties in due course. And– ” She pauses, looking him up and down. “Well, I suppose that’s it, for now. I’ll be back with some clothes for you. In the meantime, please eat – slowly, so you don’t get sick. And use the bath to clean yourself. The Prince won’t be needing it today.”

None of this comes as a surprise to Merlin except for that last addition, spoken so casually he almost misses it.

He doesn’t want to think this is a trick, but it’s just– he’s been stolen away from his bed, cleaved from his own magic, chained, stripped naked, starved, beaten; only to be saved from further cruelty by the son of the king he killed last year and struck again. His head is splitting. And now he is to fill his stomach with pottage and bread and then have a warm bath… a bath all to himself, because the prince won’t be needing it.

“Thank you,” he manages to say, throat tight.

“There’s no need for thanks, Merlin.” The Prince is lofty but brusque again as he, too, emerges from behind the screen, smoothing his tunic down. “Don’t get the wrong idea. I’ve simply no need to bathe.”

Guinevere excuses herself with one last glance between the two of them, leaving Merlin to somewhat critically eye his new master up and down. He doesn’t even have to say anything; the man is still in his mail, dirtied from a knight’s training and fresh from illness. There is sweat there clear across his brow.

“That,” the Prince adds, slowly, “is not the way you look at your betters, while we’re speaking on etiquette. Outside this chamber, it should be eyes to the ground at all times. Unless you’re directed otherwise.”

“For someone so seemingly opposed to the concept, you seem to be very clear about what it should entail."

Merlin doesn’t lower his eyes; the Prince narrows his own.

“As I said, I’ve no wish to see you strapped to the whipping post. But by all means, if you’d like to see it yourself, feel free not to listen to what we tell you.”

Which is not an unfair thing to say, really. It is clearer to Merlin now than it could ever have been otherwise that to leave the grasp of slavers was not in any way to reemerge somewhere more civil. Camelot may still be new to this practice, but Arthur Pendragon is warning him that doesn’t mean it won’t be brutal – showing him, too, where the lines are.

The Prince has been an almost unfailingly honest young man in these first few moments of their acquaintance, if also a bit of a prat, and despite the discomfort it brings, this is useful. It will help Merlin very much in planning his eventual escape.

“If I’m not to thank you for the bath,” he says, after a beat, “then I’ll thank you for the advice.”

“Fine.” A stiff nod is all the acknowledgement the Prince spares for that. “Bolt the door again, then, and don’t open it for anyone but Gwen. I’ll tell you freely that most of the standing guard and many of the knights at this point do not comport themselves honorably, and will certainly abuse you if you leave these rooms unattended. So, wash now and eat what she’s brought for you. And see that I’m not disturbed for the next hour. I have business this afternoon for which you will remain here, but then we’ll discuss what your service will look like for the foreseeable future.”

He doesn’t wait for acknowledgement, but from there turns and heads back toward the bedchamber, disappearing to the part of the room Merlin can’t see before the sounds of shifting mail and fabrics make their way out to him.

Well. All oddities aside – the honesty is unexpected but valuable, and the state of the Prince’s health and cleanliness is hardly Merlin’s business, anyway – this is far from the worst it could be. There is time ahead to get a better grasp of the layout of the castle and the quality of its remaining resources. Time to think, as well as to plan. To gather information about what’s happened on the Isle in his absence; and about the druid boy, Mordred, too.

His cheek and neck are new aches, though these rate rather low in comparison with his other pains, and at least he won’t starve here. All said, this is not a terrible way to begin an imprisonment.

Because the tides of time stop for no man, Arthur’s stolen hour is ruthlessly shortened. The midday bell tolls far sooner than he feels it should, and since he’s just given up his bath – he patently refuses to fully disrobe, or to stray too far from his sword, with his father’s killer in the room – he must quickly wash himself over the basin beside his bed.

It’s a relief to realize that the sounds of water and bathing have ceased, and to find that this is because Merlin has fallen asleep in the wooden tub. Arthur pulls his tunics and breeches from the wardrobe quickly, hyperaware of the boy’s gentle snoring. Once he’s well covered, he can take his time with the rest: selecting a surcoat humble enough to wear before who will be the hungriest of his people, though not so humble that they lose confidence in his authority; finding and lacing up his boots; and lastly, pinching some life back into his thinned cheeks, so as not to look in any way too unhealthy.

The ghosts of old nurses remind him that it is dangerous to fall asleep in any level of water, so he prods Merlin awake, eyes carefully averted from the nakedness, before he leaves. (And he deliberately ignores the quiet, bitter voice which tells him he ought to have held the dragonlord down under that water while given the chance.)

“You may sleep before the fire,” he tells the boy instead, who hums a drowsy acknowledgment, “or in the antechamber, once it’s been prepared. To rest yourself and recover from your travels is your only duty until I return. Do not cause me trouble in the meantime, Merlin, or you shall regret it.”

He means to deliver that last with a firm glare, but Merlin’s face is still very soft with sleep, and his bare shoulders are still pink with heat, and there’s something so vulnerably open about the way he blinks up at Arthur that the Prince must simply flee.

Down in the throne room, the line of petitioners is so long as to nearly wrap the room.

To hear petitions in times of extended famine can be difficult, but this is a responsibility Uther had already begun to share with Arthur before his death, and which Arthur was adamant from the start should be his own, because his uncle was terrible with the common people. (And that is indeed what likely won him the responsibility in the end, since his uncle’s intolerance of the needs and weaknesses of others could only earn him the people’s ire, and the people’s ire is not what makes Regents into Kings.)

“Good day, sire,” the Steward, whose given name is Lucan – and who is one of Arthur’s few allies among the more highly-ranked staff – mutters at the threshold… pointedly enough that Arthur knows the old man must already have several choice thoughts about Arthur’s having taken a slave. Instead of saying more, the typical announcement is made to the room: “His Highness, Crown Prince Arthur.”

There is a short silence, as there always is, while Arthur takes his place upon the throne. At his right, set at a distance far enough to be unobtrusive, the Steward follows to settle down at the small desk they’ve set up for the purpose of reasonable rationing, ready to make his notes and calculations as needed.

The few standing guards largely ignore them; only the knights who stand near to the throne, Elyan and Percival, greet Arthur with respectful nods.

Then, of course, there are the faces of the petitioners – gaunt, anxious, desperate. Hopeful, though, too.

“Let the first man come forward,” Arthur says, and quickly enough, the first becomes the fifth becomes the fifteenth.

The common theme is hunger, which can not be resolved but can at least be offset by rations from what remains of the castle granary stores, which the Steward will manage in finer detail – and which will hopefully continue to be possible through springtime. Arthur can do little but give his approval there; it isn’t until mid-afternoon, about halfway through the line of petitioners, that something arises which captures his genuine attention.

Two men step forward, one a lord, whose name is Olwen, and one a peasant, who Arthur has seen here before. Who he only remembers because he’d expected Olwen to go directly to Agravaine about the aftermath of that petition.

It started simply: “My lord, I have a wife and two young sons. We’ve not received our rations for two days. Can you spare anything for us?”

Arthur blinked down at the man – a tall brunet in the prime of his life, strong but showing signs of hunger, like everyone else – and frowned. For most of the people in this position, the rations provided by their lords were simply not enough, or were stolen, or soured unexpectedly; or perhaps they labored for no lord and were destitute. The reasons varied as to why a supplement might be needed, but not once had Arthur yet heard of food having been withheld entirely… though perhaps he should have expected such a thing, sooner or later.

“Tell me more,” he said. “From where have you come?”

Olwen is grim-faced and resolute, an older man with fine, fair features. That he does not look healthy himself does him immediate credit; so too does the fact that he’s come directly to Arthur, going so far as to petition alongside commoners in order to do so.

“Sire, I have a grievance with this man,” Olwen says, gesturing to the peasant, whose face is pallid and drawn.

As the lord explains it, the matter of the withheld rations was neither cruel nor punitive, but practical: he has only so much left to spare in the time remaining before harvest, and he can not give it to people who do not meet the terms of their obligations to him and his land. Arthur doesn’t have to verify or question this; the peasant was clear enough, at their first meeting, that he and his wife had been too ill to labor for at least several days before the rations were stopped.

When he has finished his explanation, Olwen is frowning deeply. “I want nothing from him myself, but it is an insult both to me and to you that he should come begging the crown for what he has not earned – for what all others must earn – and so, I have made him available to you for recompense.”

Arthur feels a headache tunnel sharply in behind his left eye. He leans back upon the throne, wishing it could be in any way more comfortable, and puts a valiant effort into seeming unbothered.

“I hear your grievance, Lord Olwen,” he says, evenly, “but the situation was not unknown to me when I heard his petition, and I require no recompense.”

“But sire– ”

There’s a low murmuring, a breakout of whispers across the hall, at the lord who dares to speak against a prince. Arthur, who is neither his father nor his uncle, does not appreciate that.

He waves away the misstep with a dismissive hand. “I understand your thoughts on the matter, but my decision is the same. If a man falls sick in these times and is denied food because his labor has ceased, he will not recover in order to resume that labor. If you lack the resources to provide for him, the crown can provide in your stead.” Here he pauses, though, and considers Olwen more carefully. “If, however, you do not lack the resources, to the extent that you can spare the standard rations for your people without undue burden, you are obligated to provide those whether or not they have fallen behind in their duties. I want to make that very clear to you.”

The peasant looks like he wishes nothing more than to disappear; he looks nowhere but at the stone floor, where small streaks of dirt have trekked in under the boots of the people who came before him.

Olwen’s neck has begun to flush deep crimson above its scarf.

“Sire. Are you telling me I must fund the survival of people who have stopped honoring their obligations to me?”

“I’m telling you that your tenants are not slaves,” Arthur counters, “and that if you have a grievance with any one of them, that should be brought before me to be arbitrated, and never taken out of what you have already agreed to provide for them. Camelot must remain a place of honor and integrity, no matter the circumstance, and we keep it that way by standing by our own word.”

Olwen scoffs. “This from a man who took a slave himself this morning, after standing so long against such a thing?”

There are no whispers this time. Silence sweeps the hall at that declaration, and Arthur supposes that anyone who has not already heard this news – gossip, at least, still travels fast – will shortly have heard it now.

He feels each pair of eyes upon him like little knives cutting gently into his skin.

“It is not for you to question the motives or seeming actions of your future king,” he says, “especially as a means to distract from your own. You will feed who is contracted to toil upon your land, or you will find yourself relieved of that land. Am I understood?”

Olwen’s flush has expanded into a high, angry spatter across both his cheeks. He nods, stiffly, lowering his eyes as well. (Arthur has to clear the lump from his throat, because this is how men had looked so often before his father, and to receive such a look himself is beyond sobering.)

There’s no need to raise his voice to announce the rest; it’s still as silent as death all around them. “We are living through a time of unprecedented need. You have all watched your neighbors suffer and die; you fear to suffer and die yourselves. At no point should this mean that anyone is withholding the resources of Camelot for any reason, including for their own benefit. And while we’re close to the subject, let this, too, be a warning, in these last few months before the first harvest: if I hear that any lord, or any empowered freeman, is using the threat of starvation to take advantage of the labor of their lessers, that will be the last day that lord or freeman enjoys the privileges which enabled him to do so.”

Even as he speaks these words, Arthur knows they will make him enemies – that any offending lords in particular will be more likely now to support his uncle’s efforts to usurp the throne, lest they come to face the consequences of their actions. He doesn’t care. He will not abandon his morals to assure his own ascension.

“You who work the lands of your lords,” he adds, “do not fear to make it known to me if such a thing has happened to you. You will be protected. We must not lose any more life to famine than the gods have deemed absolutely necessary.”

The peasant beside Olwen is wide-eyed now, shaking his head, moving to speak. In a gentler tone, Arthur cuts him off.

“That’s not what’s happened here, I know. It was worth saying all the same.” And to Olwen, he says, “I do appreciate the difficulties you face in providing for your people, even if it may not sound like it. Speak with the Steward before you leave, and he will see what can be spared for you. Speak with the Marshal, too, if you feel you’ll need protection in your travels home.”

A more prideful man might have declined this invitation, but as most in this room now know, these are not times in which prideful men survive. Olwen and his tenant both move off to see the Steward, and a woman and her child take their place.

By the time the room is cleared of petitioners, Arthur’s head feels like to burst. He digs hard knuckles into the eye, trying to ease it, until a throat clears at his side.

“My lord.” The Steward holds his book closed over two fingers, and Arthur already knows, by the dour expression, that what’s calculated inside does not favor them.